Table of Contents

Terrestrial Fibre Optic Infrastructure

The spread of undersea fibre optic cables around the world since the early 2000s, followed closely by the rapid spread of terrestrial fibre optic infrastructure, is nothing short of a revolution. Fibre infrastructure has spread far faster than anyone would have imagined possible. In Africa, there are perhaps only two or three countries that do not now have a national fibre optic backbone. Many countries have several. Fibre optic networks are the deep water ports of the Internet; they enable orders of magnitude greater broadband capacity than any other kind of access technology and at very low latency. For terrestrial networks in particular, the capacity of this infrastructure is so great that it is effectively a non-rival resource: access for one service provider does not diminish opportunity for other providers.

Yet operators are often reluctant to share information about their fibre networks. This reluctance betrays an apprehension that it may somehow compromise their competitive edge, but in many cases, operators have simply not considered the issue from a strategic perspective. While the majority of operators decline to publish detailed information about their fibre networks, their response stands in stark contrast to companies like Dark Fibre Africa in South Africa, and regional operator, Liquid Telecom, who readily publish maps of their fibre networks. Dark Fibre Africa stands out in the detail and ease-of-use of their maps.

Taking this information out of the narrow group of stakeholders within which it resides and opening it up to public input and discussion as open data can have multiple benefits. For example, a small rural municipality might determine from a public fibre map that it is in their interest to invest in 50 kilometres of fibre network to connect to a nearby network. A province or state might determine that their region is suffering due to a lack of fibre infrastructure investment. A school or a hospital could fund-raise for better access if they can show that a fibre optic cable is within a reasonable distance. From a national strategic perspective, fibre optic infrastructure is now comparable in terms of importance with other basic infrastructure like roads, railways, and bridges. The public needs to be aware of its existence in order to identify opportunities to connect to it and to identify gaps where more investment is needed. Making this data public can also be good for operators who can use the scope of their investment in fibre infrastructure to market their services.

What is the Open Fibre Data Standard?

The Open Fibre Data Standard or OFDS is an open data, open standards initiative. Put simply it is a standardised way of describing terrestrial fibre optic networks designed to enable effective information sharing and aggregation among telecommunication regulators and operators.

OFDS builds on the tradition of and lessons learned from important transparency initiatives such as Open Corporates and the International Aid Transparency Initiative.

Why Is Transparency for Terrestrial Fibre Optic Networks Essential?

Understanding the true extent, resiliency, and redundancy of fibre investments

Fibre optic networks are the foundation of the modern internet. They are “deep water ports”, offering orders of magnitude of greater communication capacity than any other access technology. They are the digital trade routes of the 21st century. Understanding the range, extent, and resiliency of fibre optic infrastructure, particularly at the junctions where fibre networks overlap or connect with each other is essential to forming a holistic picture of evolving internet infrastructure.

Fibre optic networks are the foundation of the modern internet. They are “deep water ports”, offering orders of magnitude of greater communication capacity than any other access technology. They are the digital trade routes of the 21st century. Understanding the range, extent, and resiliency of fibre optic infrastructure, particularly at the junctions where fibre networks overlap or connect with each other is essential to forming a holistic picture of evolving internet infrastructure.

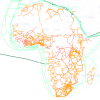

Without a common standard for describing fibre infrastructure, it is easy to miscalculate or misunderstand its extent. For example, Liquid Intelligent Technologies operate one of the largest fibre optic networks on the continent with fibre spanning from Cape Town to Cairo. Yet their network infrastructure in Tanzania, circled on the map to the left is not physically theirs but is represents long-term broadband capacity they have leased from the Tanzanian government’s National ICT Broadband Backbone (NICTBB). Someone looking at the NICTBB and Liquid’s maps might conclude that this represented two backbone networks in the country.

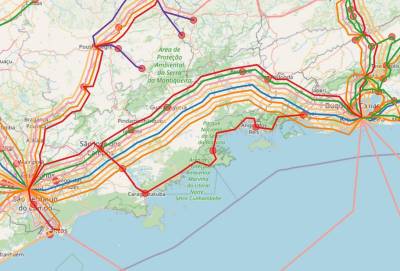

On busy routes, the issue is compounded. Looking at the map to the right which represents composite data on fibre networks collected by the Brazilian regulator. It appears that there are nine fibre networks connecting São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro but the reality is much more likely that there are 3 or 4 operators with other operators purchasing capacity or dark fibre from the actual cable owners. Without a common standard for describing fibre networks, this becomes a very challenging question to answer; a question which has implications for understanding the overall resiliency of national network infrastructure. When it comes to fibre optic networks, resiliency lies in the ability of a network to fail gracefully, seamlessly shifting traffic on to other networks. Understanding the interplay of heterogeneous fibre networks is key to understanding resiliency.

On busy routes, the issue is compounded. Looking at the map to the right which represents composite data on fibre networks collected by the Brazilian regulator. It appears that there are nine fibre networks connecting São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro but the reality is much more likely that there are 3 or 4 operators with other operators purchasing capacity or dark fibre from the actual cable owners. Without a common standard for describing fibre networks, this becomes a very challenging question to answer; a question which has implications for understanding the overall resiliency of national network infrastructure. When it comes to fibre optic networks, resiliency lies in the ability of a network to fail gracefully, seamlessly shifting traffic on to other networks. Understanding the interplay of heterogeneous fibre networks is key to understanding resiliency.

Understanding the impact of fibre optic investments

Around the world, billions of dollars have been invested in terrestrial fibre optic networks. Yet there is a dearth of available research on the impact of these investments. This is due, in large part, to the lack of readily available data on fibre network investment and deployments. An exception to this is the open data resource on African terrestrial fibre optic networks (AfTerFibre) maintained by the Network Startup Resource Center. In 2019, researchers were able to use the AfTerFibre open data resource to demonstrate a positive correlation between proximity to fibre optic networks and employment levels.

This represents the tip of the iceberg when it comes to insights that might be derived from more comprehensive and accurate information on terrestrial fibre networks. New potential areas for investigation include research into:

- Impact of climate change on network infrastructure;

- Cost effectiveness of various fibre network build-out methodologies and technologies;

- Overall network resiliency and redundancy

- Impact of cross-border connectivity investments

But fibre networks come in all sorts of shapes and sizes, from underground to aerial, from a few fibre strands to hundreds, from old technology to new.